von Prof. Dr. Jochen Bigus und Prof. Dr. Carsten Momsen

Abstract

This paper surveys current whistleblowing regulations in Europa and the U.S., and reviews theoretical and empirical findings in the economics and law & economics literature. Whistleblowing regulations differ considerably between the U.S. and Europe, for instance, with regard to the legal protection of whistleblowers and the provision of rewards. Economic theory finds that whistleblower rewards provide stronger incentives to expose corporate misconduct but may also induce unwarranted side effects. The regulator’s efforts to protect whistleblowers from retaliation mitigate personal harm but may also induce non-meritorious claims. The paper also reviews the ample empirical findings on the determinants and consequences of whistleblowing for business firms. Based on the theoretical and empirical findings, the paper provides suggestions for regulating whistleblowing.

Der Beitrag gibt einen Überblick über die aktuelle Gesetzeslage zum Whistleblowing in Europa und den USA sowie über die theoretischen und empirischen Erkenntnisse in der wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen und juristischen Literatur. Die Regelungen zum Whistleblowing unterscheiden sich zwischen den USA und Europa erheblich, zum Beispiel in Bezug auf den rechtlichen Schutz von Hinweisgebern und die Gewährung von Belohnungen. Die ökonomische Theorie besagt, dass Belohnungen für Whistleblower stärkere Anreize zur Aufdeckung von Fehlverhalten in Unternehmen bieten, aber auch ungerechtfertigte Nebeneffekte hervorrufen können. Die Bemühungen der Aufsichtsbehörden, Whistleblower vor Vergeltungsmaßnahmen zu schützen, mindern den persönlichen Schaden, können aber auch zu nicht gerechtfertigten Klagen führen. Der Beitrag gibt ebenfalls einen Überblick über die umfangreichen empirischen Erkenntnisse zu den Determinanten und Folgen von Whistleblowing für Unternehmen. Auf der Grundlage der theoretischen und empirischen Ergebnisse werden Vorschläge für die Regulierung von Whistleblowing gemacht.

I. Introduction

We define whistleblowing as “the disclosure by (former or current) organizational members of unlawful, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to affect action”.[1] We use the term “misconduct” to mean unlawful, immoral or illegitimate practices. Whistleblowing is important in the detection and combatting of organizational behavior that is undesirable from a society’s and even an organization’s perspective. Many political scandals have been uncovered by whistleblowers, e.g. the Watergate scandal in 1972 (informant: Mark Felt) and the leakage of top-secret documents of the NSA (National Security Agency) by Edward Snowden in 2013, which revealed the NSA’s massive data collection and surveillance practices.

This paper focuses on business companies, given that whistleblowers are also important in revealing corporate misconduct. Cynthia Cooper and Sherron Watkins exposed financial accounting fraud at WorldCom, and Chuck Hamel reported that the oil industry cut back precautions to protect the environment.[2] TIME magazine designated whistleblowers Persons of the Year 2002, picturing Cooper and Watkins on the front cover. Whistleblowers are important because corporate misconduct is considered to be a widespread phenomenon. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) estimates that, on average, companies lose 5 % of revenue due to fraud, totaling up to USD 4,700 billion worldwide (ACFE 2022). Very often, it is an employee of the company[3] who blows the whistle, uncovering financial or non-financial corporate misconduct at a relatively early stage[4], thus limiting the company’s monetary loss and reputational damage.[5]

Since corporate insiders are often better and earlier able to discover corporate misconduct than private or public enforcement agencies, whistleblowing saves expected costs resulting from misconduct, including reputational damage, and enforcement costs.[6] However, companies or colleagues often consider whistleblowers to be traitors such that whistleblowers experience personal harm and retaliation, e.g. social exclusion, job loss or threats voiced by the employer or colleagues. Given the potentially huge benefits for the company, but also for society at large, in stopping corporate misconduct, many countries started legal initiatives to protect and/or incentivize whistleblowers, e.g. the False Claims Act in the U.S. and the Whistleblower Protection Directive in the EU.

The aim of this paper is fourfold. First, it presents a current survey of how whistleblowing regulations differ between the U.S. and Europe, e.g. with regard to the legal protection of whistleblowers, the provision of rewards, and the liability of whistleblowers for non-meritorious or frivolous claims. Second, the paper reviews findings from economic theory, including the benefits of whistleblower rewards and whistleblower protection, but also unwarranted side effects. Third, this article presents a survey of the extensive empirical findings on the determinants and consequences of whistleblowing. Fourth, we discuss how the empirical evidence matches the findings of the theoretical research and draw conclusions for law-making on whistleblowing.

Unlike previous reviews of the whistleblowing literature,[7] we not only provide an update of the literature, but also (1) explicitly consider theoretical findings from the economics and law & economics literature and (2) link them to the empirical evidence, as well as to the question of how to design whistleblowing laws. Fourth, while previous reviews placed greater emphasis on the link between whistleblowing intentions and the whistleblower’s individual attributes, we focus more on the organizational and institutional drivers, as well as the consequences of whistleblowing and the regulation of whistleblowing.

In business, economics and law & economics, relevant research is usually published in journals. We searched for peer-reviewed journal publications using the terms “whistleblow**” and “whistle-blow**” in the title in the Business Source Premier database of EBSCOhost. The search yielded 564 papers from which we selected 88 publications in accounting, finance or management journals with a B-, A- or A+ rating according to the journal ranking of the German Academic Association for Business Research (VHB-Jourqual 3).[8]

Section 2 surveys the legal provisions on whistleblowing in the U.S. and in Europe. Section 3 presents theoretical findings of the economics literature and the law & economics literature. Section 4 reviews the empirical evidence of the determinants and consequences of whistleblowing. Section 5 concludes how the insights from the (law &) economics literature can help shape whistleblowing regulation.

II. Legal provisions in the U.S. and in Europe

1. Legal protection of whistleblowers

The concept of legal protection shows some crucial differences between Europe and the U.S. One systemic reason for this difference is that in the U.S., whistleblowers are seen as undercover agents conducting their own investigations or actively using investigative measures, none of which is common in Europe or Germany in particular, where whistleblowers are simply seen as witnesses.[9]

In addition, a specific bar of whistleblower lawyers has emerged who help protect whistleblowers against the state and the company, and who more or less conduct independent criminal investigations instead of the state prosecutor – the very idea of “qui tam” legislation. No such comparable specialized legal protection exists in Europe.

a) Legal protection within the European Union

The EU began to address whistleblowing earlier than Germany, inspired by the success of the much more established U.S. whistleblowing law, which began to affect the EU and its citizens from 2002 onwards.[10] Influenced by the U.S., whistleblowing can be seen as “a functional element in the reduction of information deficits within law enforcement” in the subsequently enacted Union law.[11]

The EU started to implement whistleblowing regulations in directives mainly targeted at different areas, mostly protecting the whistleblower by obligating authorities and companies to integrate confidential hotlines as well as anti-discrimination measures within labor law.[12]

In addition, the European Court for Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that whistleblowers must be protected in their freedom of speech guaranteed by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). As a result, the firm cannot be prosecuted on the grounds of labor discrimination within the Member States, following internal or external whistleblowing, i.e. whistleblowing to recipients within or outside the company.[13] It is not a violation of Article 10 ECHR to implement the relatively strong privilege of internal whistleblowing (as the German Federal Labor Court does, for instance).[14]

aa) Directive on the Protection of Trade Secrets

In 2016, the EU passed the Directive on the Protection of Trade Secrets (Directive (EU) 2016/943), protecting the interests of institutions in the confidentiality of their internal information and data, and reacting to the diverging levels of protection within the Member States, which negatively affected competition and innovation.[15]

According to Article 2(1) of Directive (EU) 2016/943, trade secrets are secret information that has a commercial value based on its confidentiality (not known or easily accessible to the usual group of people) and that is subject to reasonable security measures.

Trade secrets are protected against unlawful acquisition, disclosure and use.[16] The motives behind these actions are irrelevant concerning their assessment as a breach.[17] Generally, this also covers whistleblowing. If trade secrets are breached, the Member States are responsible for implementing (fair) measures, procedures and remedies.[18]

Unlawful acquisition means the acquisition of trade secrets by means of unauthorized access to, appropriation of, or copying of any documents or other objects or data that are lawfully under the control of the holder, and that contain information about the trade secret, or by means of any other action that is considered contrary to honest commercial practices.

The disclosure or use of a trade secret is unlawful whenever carried out, without the consent of the holder, by a person who acquired the trade secret unlawfully or who was in breach of a (confidentiality) agreement,[19] or if this is true not for the disclosing person but for a third party from whom the whistleblower received the information.

The question is therefore under which circumstances whistleblowing is classified as unlawful or unauthorized. Article 5(b) of Directive (EU) 2016/943 tries to balance out the different interests, allowing whistleblowing as long as it is subjectively in the general public interest. There is no distinction between external and internal whistleblowing for this exemption.[20]

bb) Directive on the Protection of Reporting Persons

The Directive on the Protection of Reporting Persons (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) was implemented in 2019 and is the most extensive regulation of whistleblowing in the EU to date. The Member States were obligated to transpose this Directive into national law by the end of 2021 (which some Member States, including Germany, failed to achieve). The aim of the Directive is to enhance the enforcement of Union law by providing for a high level of whistleblower protection and improving the general structural framework of whistleblowing, helping to detect and prevent breaches.[21] The Directive interprets whistleblowing in a very broad sense:

Protected are all reports of breaches of Union law (all of which are listed in the Directive) and all connected activities which the whistleblower in good faith deems necessary for the disclosure, e.g. the method of the preparing the search for information which itself may actually constitute a breach of the labor contract as long as the acquisition itself does not breach national criminal codes,[22] such as §§ 123, 202a of the German Criminal Code (StGB).

Although EU legislation targets the interests of the Union, there are several extensions. The subject of whistleblowing cannot only be actual breaches of Union law, but also prospective, very probable ones,[23] as well as any misconduct which does not directly constitute a breach, but defeats the object or purpose of any Union law.[24] Protected whistleblowers are all employees in the common sense as well as members of internal bodies, self-employed persons, corporate bodies, contracting parties and their employers,[25] but not persons under a confidentiality agreement, e.g. lawyers.[26]

Whistleblowers have a choice between internal and external whistleblowing. This effectively leads to an incentive for employers to implement effective internal whistleblowing systems because in fact it could cause more damage to the organization if the whistleblower reports externally just because there are no effective confidential internal systems.[27] If they do decide to blow the whistle externally, it needs to be reported to official (whistleblowing) authorities. If whistleblowers report to the media or the public, they are only protected if they act in good faith concerning an imminent or manifest danger to the public interest, their own prosecution, or the ineffectiveness of the authorities[28] and wait an appropriate period of time during which the authorities remain inactive.

The whistleblower also needs to act in good faith concerning the actual existence of the misconduct. Apart from that, however, the individual motives are completely irrelevant with regard to achieving protection. This is different in some other Member States, e.g. Germany (see below).

If these criteria are met, the whistleblower qualifies for protection against any kind of retaliation. This means anti-discrimination measures within labor law,[29] e.g. dismissal and other disadvantages such as demotion, withholding of promotion, a harmful change in working conditions, harassment, harm to one’s reputation, as well as industry-wide blacklisting, etc.[30]

In addition, Directive-compliant whistleblowing is a universal justification factor, leading to the exclusion of civil liability such as damages or criminal liability.[31] This is supplemented by an evidentiary presumption that subsequent reprisals against the whistleblower are a prohibited response to the whistleblowing.[32]

In addition to these protective measures, the Directive encourages institutional to promote whistleblowing. Any private or public institution with 50 or more employees is obligated to establish internal reporting channels. These organizations need to meet the following criteria: (1) guarantee of confidentiality, (2) any report must be documented properly and must set in motion subsequent measures such as internal investigations and, if necessary, penalties.[33] The government is obligated to establish external reporting channels within the authorities, meaning that special whistleblowing institutions provide confidentiality and integrity.[34]

Another important part of the Directive (also seemingly inspired by the U.S., see above) are the specific penalties that can be imposed on people who actively try to hinder whistleblowing, thus making sure that whistleblowing is encouraged and protected in toto.[35]

b) Legal protection in Germany

Germany[36] essentially has a conflicted relationship with the disclosure of other people’s wrongdoing because of the country’s past (the Third Reich and the German Democratic Republic), involving the Stasi, the denunciation of Jewish citizens and general strict surveillance by the state.[37] For this reason, Germany takes a completely different approach to privacy than the U.S.[38] The public interest in disclosure must be weighed against the private interests of privacy and confidentiality.

aa) Labor law

Until spring 2023, the most important protection for whistleblowers was established under labor law. In 2001, the German Federal Constitutional Court (GFCC) ruled that every citizen has a basic right to exercise civic rights regarding external whistleblowing,[39] meaning that whistleblowing employees can only be subject to labor consequences to a limited extent (even if the information was wrong). The court stated that the public interest in transparency and effective criminal justice as well as the employee’s freedom of speech and right to exercise civic rights outweighed the interests of companies in ensuring the loyalty of their employees and the confidentiality of their data within their basic right to professional freedom (Article 12 of the Basic Law (GG).[40]

To achieve a balance of interests, the Federal Labor Court set out criteria for “lege artis” whistleblowing. Of course, it would be possible to explicitly implement an obligation for internal whistleblowing in the labor contract,[41] but this is also part of the general duty of good faith imposed by the labor agreement in any case. However, the employee is obligated to report misconduct internally first before taking the matter to the authorities, and generally to give notification of important events within the company and prevent damage to the company.[42] This is only true as long as internal reporting is still reasonable – which is not the case with major crimes, crimes perpetrated by the employer, any statutory duty to report to authorities, or a lack of measures following initial internal reporting.[43] Naturally, it is within the company’s discretion to decide how disclosure is to be executed (e.g. through an internal compliance management system (CMS)). If the employee breaches this duty, external whistleblowing can constitute a breach of contract and grounds for termination.[44] This was modified, however, by a new labor protection regulation based on an ECHR verdict giving employees the right to report to the authorities if the misconduct was potentially a crime or if no internal investigation was necessary.[45]

Companies can of course prevent external whistleblowing from occurring themselves by setting incentives for internal whistleblowing in the form of confidential, anonymous reporting channels, ensuring that whistleblowers are not hindered by social effects or the risk of dismissal.[46] Another option would be to follow the U.S. example and offer rewards for internal reporting (leading to the question of the appropriate amount, factoring in a risk of abuse, and the inclusion of co-perpetrators).[47] In addition, the participation rights of the workers’ council concerning surveillance and data protection requirements need to be taken into consideration when establishing such internal reporting channels.[48]

bb) Criminal law

For the rest, it may constitute a crime to disclose confidential information. In fact, the risk of making oneself criminally liable by whistleblowing is much higher in Germany than in the U.S. But in the interests of a balanced legal situation, it is questionable whether this should not be justified if certain criteria are met. Under the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch, StGB), a whistleblower who knowingly reports untrue information and harms the organization’s reputation can be held responsible for any damage caused, theoretically including reputational damage as grounds for compensation claims in addition to criminal sanctions.[49] If the data was obtained illegally by bypassing a security system, § 202a StGB is applicable. The disclosure of information by persons under a confidentiality agreement, such as doctors, is a crime under § 203 StGB. However, these statutes do not apply to employees who obtained information as part of their job.

For this reason, the Directive (EU) 2016/943 was transposed into German law by the Trade Secrets Protection Act (Geschäftsgeheimnisgesetz, GeschGehG) in 2019. This act primarily regulates civil liability and legal remedies of the holder against the violator of confidentiality.[50] In other words, the act does not aim to protect or encourage whistleblowing, but to hold whistleblowers responsible for potential damages caused by the disclosure.

For the rest, the transfer of trade secrets is explicitly considered a crime that may be justified under certain conditions. It is important to note that not all forms of whistleblowing are included in this safe harbor of justification – it only applies to the disclosure of “trade secrets”, not any kind of misconduct, meaning that even the current protection is very narrow. The regulations also only apply to directly employed whistleblowers, because only such staff can be contractually obligated to nondisclosure.[51] This is much more restrictive than the EU Directive (and the general terminology, see above), which also applies to persons only indirectly related to the organizations. It may be necessary to interpret the regulations in a Union-friendly, uniform way and to apply protection to non-included whistleblowers who are in good faith concerning the need for reporting under the Directive.[52]

A trade secret is defined in the GeschGehG in the same way as in the EU Directive.[53] A trade secret has a commercial value if its disclosure has the potential to harm the holder.[54] Information about unlawful actions is therefore included.[55] Some argue that the interest in keeping information confidential loses it legitimation if the protected information concerns unlawful behavior. However, interpreting the definition in this way may constitute a breach of the EU Directive, which systematically protects even knowledge of unlawful actions, again leading to the need for § 2 GeschGehG to be interpreted in a Union-friendly way, legitimation being presumed.[56] § 4 GeschGehG prohibits the unlawful acquisition, use and disclosure of trade secrets, the disclosure only being included if the acquisition was unlawful or it itself breached an obligation deriving, e.g. from the labor agreement. § 23 GeschGehG regulates criminal liability, applying to the acquisition and disclosure of trade secrets if motivated by certain reasons, these reasons being the dividing point between civil and criminal liability.[57] This includes the own furthering to the disadvantage of the organization concerned.

Whistleblowing constitutes criminal behavior if the information reported is a trade secret and the whistleblower acts on the grounds mentioned above. A sentence can even be increased if there was commercial coverage or if the trade secret was used abroad. Even an attempt to blow the whistle constitutes grounds for criminal liability.[58]

When conflicting interests are balanced, whistleblowing may be justified, see § 5 Nr. 2 GeschGehG. If the disclosure refers to unlawful, professional, or otherwise unethical misconduct of a certain significance that actually occurred and that is able to protect public interests (meaning its ability to immediately and effectively end the misconduct)[59], whistleblowing is justified, even if the criteria of § 23 GeschGehG are met.[60]

Neither EU nor German regulations explicitly state whether they are applicable to co-perpetrators. On the contrary, motives are factored in to the justification, which might mean that people who disclose only to lower their sentence might not even be included in the definition. However, explicit protection exists for principal witnesses (§ 46b StGB) if co-perpetrators voluntarily disclose crimes of a certain significance[61] within the context of their own crime (which needs to be threatened with a relatively high prison sentence) and this disclosure makes a successful contribution to the investigation.[62] A number of specific regulations are also in place in certain legal areas such as narcotics or terrorist organizations.[63] It may also be useful to explicitly regulate these areas with regard to whistleblowing, too.[64]

cc) The 2023 German Whistleblower Protection Act (Hinweisgeberschutzgesetz, HinSchG)

In general, the awareness of a need for action to balance all the different interests at play has increased in Germany, leading to two relevant draft bills.

(1) The “Draft Bill to Strengthen Economic Integrity” (2020) and the first Draft of the Whistleblower Protection Act (2021)

The German approach to protect whistleblowers should originally have been based on two pillars: corporate liability and the institutionalization of whistleblowing. The main part, a draft of the Corporate Sanctions Act (Entwurf Verbandssanktionengesetz, VerSanG-E),[65] was published in June 2020 as a result of two rulings, one by the Federal Court of Justice in 2017 (the so-called “Panzerhaubitzen”- decision),[66] and the other by the GFCC in 2018 (so-called Jones-Day).

Since these two decisions conflicted regarding the relevance of CMS in state-driven investigations and the amount of state-imposed sanctions, the need for clear legal regulation became apparent.

First, the draft of the VerSanG implemented the so-called “Legalitätsprinzip” (“principle of legality”), leading to an obligation for authorities to investigate as soon as a whistleblower reports any relevant misconduct.[67] This differs from the normally prevailing “principle of opportunity” in the field of misdemeanor law, giving the authorities the opportunity to prosecute if they deem it necessary. [68] Second, the bill was designed to strengthen internal CMS. This would have inherently promoted whistleblowing, since a confidential, effective internal procedure protects whistleblowers and therefore gives prospective whistleblowers an incentive to blow the whistle. To implement CMS, the draft provided a standard which, where met, would have led to lower sanctions. Unfortunately, despite its potential for encouraging and indirectly protecting whistleblowers, the bill was rejected by the legislative because the coalition parties were unable to agree on the specifics.

Seeking to transform the Directive (EU) 2019/1937 by the end of 2021, the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection also submitted a “Draft Bill of the Whistleblower Protection Act”.

Besides offering the direct protection of whistleblowers as individuals, the idea behind the draft was to promote whistleblowing as an institution. The aim was to impose a duty for companies with more than 50 employees or certain kinds of companies[69] to implement internal whistleblowing hotlines, and for the state to establish an external independent reporting point within the authorities.[70] Both the external and the internal reporting points were supposed to fulfill certain criteria, e.g. confidentiality and anonymity, documentation, and the design of a procedure and subsequent measures.[71]

(2) The 2023 Whistleblower Protection Act

Both drafts failed due to intense counter lobbying based on the theory that an increase in costs for establishing the CMS measures would negatively impact the competitiveness of German corporations from an international perspective.[72]

It also became very apparent that the two subjects – whistleblower protection and corporate liability – are closely interrelated. Nevertheless, the new Act still tries to regulate one aspect without any regard for the other. This structural deficit very much impairs efforts to establish an effective whistleblower protection system in Germany.

(a) Key regulations

The new law[73] did not proceed very far from the 2021 draft. In fact, it even sets lower standards than the draft in some places.

Section 1 defines applicability on a personal and institutional level. Section 2[74] defines the material scope more broadly than prescribed by the EU Directive since not only breaches of Union law but basically all crimes or breaches of law can be covered by the scope of the law.

Section 7 equalizes internal and external reporting in accordance with the EU Directive – whistleblowers can opt to report to an internal or external reporting point. These reporting points must meet certain requirements and follow specified procedures laid down in the law. Reporting points are required to follow up on reports and check their validity, as well as act with confidentiality. The obligation exists for companies with more than 50 employees, which includes relatively small businesses. This may be viewed critically due to the cost of implementing such channels. However, the smaller the business, the greater the dependence of employees and the need for such reporting points. Hence, one could argue that there is a gap in protection, given that the obligation starts at 50 employees.

Employees do not have the right to disclose information to the public – this has other requirements put forth in Section 32: Whistleblowers must have at least tried to submit an internal report without any follow-up action or reason to believe that such a report will pose a threat to public interest, of reprisals or the evidence as it might lead to covering the misconduct by the corporation.

External reports need to be submitted to a special reporting office at the Federal Office of Justice. This office needs to work independently and with confidentiality.

(b) Gaps in protection

There are still some significant regulatory gaps. For example, Section 5 explicitly states that matters of national security or classified information starting at the second to lowest level of classification do not fall under the scope of the law.

Furthermore, there is no obligation to provide anonymous reporting channels at either the internal or external reporting points. External reporting points are even obliged to prioritize non-anonymous reports, even though there is no convincing empirical data showing that anonymous reports are less credible or have less merit. This may effectively lead to fewer reports, especially in high-profile cases or in cases where the disclosing person is part of the misconduct at issue. The law also failed to make use of the opportunity to allow whistleblowers to receive damages based on immaterial reprisals such as bullying.

Finally, the fine for misdemeanors such as failing to implement an internal reporting point, trying to prevent reports from being submitted, or punishing whistleblowers was halved from EUR 100,000 in the first draft to EUR 50,000, which to large companies is peanuts. In the European perspective, some other whistleblower protection laws impose much higher fees or even imprisonment.[75] It might not even be the yearly income of the whistleblower they illegally dismiss after a report.

c) Legal framework in the United States

As mentioned at the beginning, the U.S. has been dealing with the subject of whistleblowing since the late 1800s, signing over 60 respective bills into law.[76] This has even increased in recent years due to the federal legislator trying to effectively prosecute violations of federal law. Whistleblowing regulations are used for this purpose by enabling the authorities to confidentially receive information and implicate internal whistleblowing systems while also establishing specific lay-off and discrimination protection law. One important reason is that typical corporate crimes are the subject of federal legislation. Moreover, key law enforcement and regulatory agencies have been established (SEC, FDIC, FINRA, CFPB, EPA[77]) and endowed with investigative and limited prosecutorial powers.[78]

aa) Criminal liability

There are a few offenses in the U.S. Criminal Code that may be applicable to whistleblowing (depending on the individual circumstances). The main difference to the European directive and, e.g. the German law, is that there is no explicit protection of secrets, which generally exposes whistleblowing to the serious risk of being classified as criminal conduct.[79]

“Theft” might be applicable in the case where a whistleblower unlawfully takes or exercises unlawful control over movable property of another with the purpose of depriving them thereof; meaning cases in which they, e.g. remove documents or other evidence from the organization’s control with the purpose of making it public. It even constitutes a crime of the third degree if the property taken is of a public record, writing or instrument kept, filed, or deposited according to law with or in the keeping of any public office or public servant. Again, slightly different from Europe, intent or at least bad faith is necessary for criminal liability to apply.

Apart from the General U.S. Criminal Code, whistleblowers may be held liable under the Espionage Act of 1917. This act applies to government employees who communicate classified information related to national defense. This can lead to severe sentences for “whistleblowing in the interest of public” or governmental whistleblowing.

bb) Whistleblower protection

Whistleblower protection in the U.S. does not focus on protecting the whistleblower from criminal liability, but on labor law or incentivizing reports. This is true at both federal and state level. At the state level, e.g. there are exceptions to the “employment at will doctrine”, which states that “an employer can discharge an employee without notice and without cause unless the duration of the employment … is specified in an employment contract”, and broad protection regulations as well as regulations limited to specific areas of public life.

The instruments used are anti-retaliation and reward-based laws. Since the anti-retaliation laws (despite being important) had little success in providing incentives for whistleblowing, greater emphasis has been placed on rewarding recently. Although convincing in theory, anti-retaliation is usually in effective in reality because reputation and work relationships are usually irrevocably harmed, at least when the identity of the whistleblower becomes public.

cc) Anti-retaliation in U.S. law

In 1989, the Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA) was signed into law.[80] It is an important example of an anti-retaliation law, given that it protects employees or applicants from personnel actions based on “any disclosure of information that they reasonably believe evidences a violation of any law, rule or regulation; gross mismanagement; gross waste of funds; an abuse of authority; or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety”.

Another anti-retaliation law is the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002, which tightened the requirements for official representatives and auditors to provide proper financial reporting within publicly traded companies. The act is supposed to set an extrinsic motive for organizations to prevent misconduct.[81] The scope of protected whistleblowing is limited to accounting and auditing practices. Section 301 of the SOX requires an anonymous reporting system modified to the specific characteristics of each organization and internal audit committees within which employees can report dubious practices within that scope. The system must not just facilitate the anonymous reporting of misconduct – it can also impose a duty for employees to report identified or assumed misconduct by corporate governance.[82] In addition, any organization within the scope of the law needs to implement a code of ethics that promotes whistleblowing. Whistleblowers are protected from dismissal and other discriminations as a result of reporting misconduct.

Furthermore, anyone who attempts to intimidate (prospective) whistleblowers or interfere with their intention to report misconduct can be held criminally liable and sanctioned with a fine or imprisonment of up to ten years.

Last but not least, the U.S. protects whistleblowers indirectly by means of sentencing guidelines (USSC Chapter XIII).[83] Courts can reduce sanctions on companies if they have an effective compliance management system (CMS) installed. For the system to be “effective”, it must meet certain requirements listed in the guidelines, including anonymity or confidentiality, protection from retaliation, and possibilities to report any kind of criminal activity.[84]

Moreover, self-disclosure of individuals and entities as well as cooperation with the Department of Justice (DOJ) are incentivized by way of reducing penalties or giving public acknowledgement. Criteria are proactiveness, punctuality and voluntariness.[85]

2. Rewards for whistleblowers

As highlighted above, the idea of awarding whistleblowers a bounty or reward is one of the most influential systemic differences between the U.S. and Europe.

This instrument already became part of the first and, to this day most important, U.S. whistleblower law (and in many ways, the basis for subsequent laws): the False Claims Act (FCA, 1863).[86] The FCA is still in power and provides financial incentives for those who disclose misconduct of others. It can therefore be categorized as a mainly reward-based law. Although the FCA is a federal law, many states chose to implement versions of it at their level.

The FCA allows so-called “Qui-tam lawsuits”, meaning that private citizens, called “relators” (whistleblowers), are authorized to sue others in civil court if they have information of fraudulent behavior damaging the government under 31 U.S.C. § 3729, which states that it is illegal to submit “false or fraudulent claims for payment or approval”.

If a qui-tam lawsuit is successful due primarily to information disclosed by the whistleblowers and the government is able to recover damages, the suing citizen is entitled to 15-30 % of the recovery. The amount awarded depends on whether the government joined the case within 60 days, the quality of the whistleblowers’ contribution, and the significance of the danger for the public safety. If the success is not due primarily to the whistleblower’s information, they will still be entitled to up to 10 % of the recovery. The whistleblower’s motives play no role with regard to the reward, which is limited in its amount. No reward is awarded if the whistleblower “planned and initiated” the fraudulent behavior; or, if she is criminally convicted for participating in it. Remarkably, although the status of a co-perpetrator is not relevant when it comes to protection, it may be when rewards are concerned! If the claim was false and the whistleblower was in bad faith, they can be obligated to pay the fees and expenses of the accused (if the government did not join the case).

To protect the whistleblower and to secure an effective investigation, the lawsuit is filed “under seal”, meaning that it is kept confidential for 60 days, even from the accused party. It can only be dismissed by a joint, reasoned dismissal by the Attorney General and the court. Beyond that, the FCA protects whistleblowers from reprisals by granting them “necessary” damages which they suffered because of a legitimate qui-tam lawsuit. This includes a right to reinstatement, double back pay as well as the reimbursement of their costs and fees. The U.S. government collected around USD 3.7 billion from Qui-tam cases under the FCA, awarding USD 392 million to whistleblowers. This can be described as a success for both parties.[87]

Whereas the FCA model gives the whistleblower great leeway in how to conduct “his” investigation, most other reward-based laws, such as the Securities Exchange Act (SEA) of 1934 or the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) of 1936, do not require the whistleblower to pursue the claim themselves. The laws simply allow the authorities to use the information provided and to reward the whistleblower with part of the fine or recovery, using a cash-for-information approach. This varies between the many different laws that regulate whistleblowing programs for various areas of public life. Most of the laws do, however, include a possibility for the whistleblower to privately sue their employer for reprisals after reporting misconduct if they met all the criteria of the law for legitimate whistleblowing.

A more recent example of a whistleblower law is the Dodd–Frank Act (DFA), which was signed into law in 2010, replacing the Insider Trading and Securities Enforcement Act of 1988, which rewarded reporting about insider trading, but was more or less ineffective because it was not generous enough.

Under the scope of the DFA, the Whistleblower is awarded 10-30 % of the sanctioned fine or money collected, creating a bounty program for internal and external whistleblowing concerning violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. To be eligible for the reward, the report must be voluntary and originate from first-hand knowledge, meaning that the information may not be public knowledge. On the other hand, the disclosure may not violate confidentiality obligations. The individual motives behind the report are irrelevant for eligibility. The report may be submitted directly to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or internally within a compliance management system, which then reports to the SEC. In this way, the U.S. awarded USD 138 million to whistleblowers in 2018.[88] In 2021, the SEC awarded USD 564 million to 108 whistleblowers, the largest amount awarded and the largest number of individuals rewarded in a single year.[89] In 2022, the SEC Whistleblower Program continued its momentum, issuing USD 230 million in awards to 103 whistleblowers. In 2023, one single whistleblower was awarded USD 279 million.[90]

Nevertheless, in 2018 the then-President Trump signed the “Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act”, exempting dozens of U.S. banks under a USD 250 billion asset threshold from the Dodd–Frank Act’s banking regulations.[91]

In the area of money laundering, new provisions of the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA, 2020) have been implemented. Among other things, the act includes new whistleblowing regulations, which reward the whistleblower with up to 30 % of the sanction later imposed. Again, the criteria are voluntariness of the internal or external disclosure, the originality of the information, and a minimum resulting sanction of USD 1 million. Whistleblowers are protected from dismissal and discrimination by granting compensatory damages or reinstatement, alongside obligations of non-disclosure for the authorities involved. The role model for this aspect was a similar program by the SEC. In contrast to the AMLA, however, the latter program does not include compliance officers, auditors, or legal advisors, meaning that even “insiders” are motivated to report misconduct through rewards under the AMLA.[92]

3. Liability for non-meritorious or frivolous whistleblowing

Frivolous whistleblowing can be seen as bullying, insulting, or even slandering and defaming. The whistleblower is then culpable for wrongdoing under the respective jurisdictions. Of course, if legally protected information has been disclosed, this is seen as an offense under most national criminal laws, and is addressed in the EU. In such cases, there is no legal protection for whistleblowers. Last but not least, unethical whistleblowers lose specific labor law protection from dismissal, etc. For example, if an employee raises malicious, vexatious or knowingly untrue concerns in order to harm their colleagues they will face internal disciplinary action depending, e.g. on the relevant CMS. This action could result in dismissal unless the whistleblower is able to demonstrate a reasonable belief that the concern was raised in the public interest.[93]

4. Whistleblower attorneys – stakeholders with particular economic interests

Although the EU in general (and Germany in particular) has taken a number of steps forward, there is still a substantial difference in how whistleblowing cases are handled compared to in the U.S.[94] However, even whistleblowing regulations in the U.S. can be described as a “patchwork”. Key elements are: incentives in the form of participation in sanctions (in part through privatized pursuit); effective CMS, and the protection from reprisal of any kind.

Nevertheless, the more sophisticated U.S. practice brings in a new group of stakeholders that have their own substantial economic interests – whistleblower attorneys. From their perspective: “Whistleblowers with the use of a whistleblower lawyer play a crucial role in ensuring that entities are held accountable for their actions when they run afoul of statutes like the False Claims Act, Sarbanes-Oxley, Anti-Money Laundering Statutes and many more statutes that economically incentivize individuals to blow the whistle.”[95]

In qui-tam cases, this means potentially enormous fee expectations for lawyers. The FCA and a number of other whistleblower statutes require that a whistleblower employs a whistleblower lawyer, for good reason. In an FCA case, “the whistleblower (or ‘relator’) is a proxy for the government, and the government can decide to some extent who can serve as its ambassador with the claim. Therefore, they do not want pro se litigants bringing their own actions, so as to lessen the chance of creating bad law for the government and future whistleblowers. Another extremely important reason why whistleblowers should use a whistleblower attorney is that some statutes enable anonymity with the use of whistleblower counsel, such as blowing the whistle on securities violations (like insider trading), commodities violation (like price fixing), money laundering, and many more. There can be a comfort in anonymity as some whistleblowers face many risks when they step forward to report wrongdoing. They may face retaliation from their employer, including harassment, demotion, or even termination. They may also face legal challenges and penalties, especially if they are reporting on a large, complex, or powerful organization (…)”.[96] At best, professional litigation will ensure that the case is kept confidential as long as useful and tolerated by the enforcement authority.

However, the participation of specialized attorneys usually strengthens the whistleblower’s position. Due to the dependency of salary and damage volume uncovered by the whistleblower (and the amount rewarded), however, this structure tends to widen the scope of the case as far as possible. Since it makes internal negotiations more difficult, it has a potential to increase the costs incurred by the company significantly – as well as the whistleblower’s costs if he fails to succeed.

III. Whistleblowing: insights from economic theory

1. The preference for internal or external whistleblowing

Internal whistleblowing implies that an employee reports misconduct to corporate recipients only, such as superiors, board members, auditors or audit committee members. As mentioned above, we refer to external whistleblowing when an employee exposes corporate misconduct to recipients outside the company, such as enforcement agencies or the media.

Whistleblowing is economically desirable if its cost-benefit ratio is more favorable than that of other forms of law enforcement, e.g. by public enforcement agencies,[97] or when it complements public or private enforcement. For instance, limited funding of enforcement bodies may only allow them to react after misconduct has already occurred, but not to proactively screen potential cases of misconduct.[98] (Reliable) external whistleblowing tends to reduce the costs of proactive screening since the enforcement body is better able to identify possible cases of future misconduct. This increases the likelihood of (early) fraud detection and also reduces the expected benefits of wrongdoers.

By definition, internal whistleblowing does not support a government’s proactive enforcement. Nonetheless, as with external whistleblowing, reliable internal reporting helps reduce the damage to the company from misconduct and mitigates incentives for misconduct. In contrast to external whistleblowing, internal reporting does not impair the company’s reputation in capital and product markets unless it is leaked. However, internal whistleblowing requires that the recipient is interested in halting the misconduct. If colleagues, superiors and/or top management are involved in misconduct or ignore it, internal whistleblowing is unlikely to change anything. External whistleblowing may then be the only option, especially when only a few or no co-workers support the whistleblower’s claim. However, external whistleblowing most likely results in significant reputation losses of the company, even if it turns out that the claims were not substantiated.

2. Rewards for whistleblowing

The False Claims Act and the Dodd–Frank Act in the U.S. allow a reward for whistleblowing, often expressed as a proportional share of the monetary penalty charged to the company, e.g. as damage compensation.[99] As mentioned above, rewards can be substantial. For instance, the Internal Revenue Service paid USD 104 million to a whistleblower for uncovering tax evasion schemes that UBS recommended to its US-American clients.[100] On May 5, 2023, the SEC announced the largest whistleblower reward ever paid out (USD 279 million).[101] 30 % of the OECD countries provide incentives for whistleblowers, such as financial rewards, expediency of the process, or follow-up mechanisms.[102] The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners provides worldwide evidence that about 15 % of the organizations surveyed offer whistleblowing rewards.[103] In contrast to the U.S., there are currently, with the exception of Ireland, no financial rewards provided by enforcement agencies in Europe.[104] What are the insights from the theoretical literature on rewarding whistleblowers?

Depoorter and de Mot acknowledge that a reward provides incentives to expose misconduct. However, they also highlight two problems related to rewards offered by enforcement agencies in the U.S.[105] First, rewards provide no incentive to expose corporate misconduct as soon as it is observed by the whistleblower. From society’s perspective, misconduct should be halted as early as possible. Nonetheless, insiders will not blow the whistle immediately, because a reward will only be paid out if the sufficiently substantiated allegations meet a certain evidence threshold. Moreover, in the U.S., the proportional share of the penalty rewarded to the whistleblower tends to increase with the size of the damages caused by the misconduct.[106] This might provide perverse incentives, especially when the whistleblower faces no competition from other insiders. The insider may wait to uncover corporate misconduct because waiting increases the size of the fraud, and that of the expected reward. Employees who are motivated by loyalty only may report earlier.

Still, one might argue that insiders are unlikely to expose corporate misconduct when there is no reward at all. This is because whistleblowers experience personal costs, including the trouble and discomfort of reporting, but especially retaliation by the employer, by colleagues[107] or by the wrongdoer herself.[108] Dyck, Morse & Zingales therefore state: “…the surprising part is not that most employees do not talk, but that some talk at all.”[109] On a corporate level, whistleblower rewarding seem to speed up the discovery of fraud. The ACFE reported that the median duration of fraud is eight months if the organization offers a reward, and 13 months otherwise.[110]

Givati provides a model on the optimal reward depending not only on the whistleblower’s personal costs, but also on the risk of false reporting.[111] He argues that the presence of rewards may induce insiders to falsely accuse the company of misconduct, especially when there are no effective sanctions for misreporting. Insiders may then be able to fabricate evidence, inducing a penalty for the company and a reward for the insider. In fact, with the current regulation in the SOX and the Dodd–Frank Act, whistleblowers are not required to prove their allegations, but only to show reasonable belief.[112] Thus, it comes as no surprise that Kuang, Lee and Qin find that in the period 2004-2014, only 237 out of 770 external whistleblower reports on financial misconduct of U.S. listed companies were substantiated.[113]

The higher the personal costs, the higher the reward must be in order to encourage the insider to uncover corporate misconduct. There is a limit, though: When personal costs are sufficiently high relative to the expected damages caused by the misconduct, the optimal strategy is not to grant a reward because the risk of false reporting increases too much then. Thus, Givati finds that the optimal reward increases with relatively low personal costs, but drops to zero when personal costs are too high.[114]

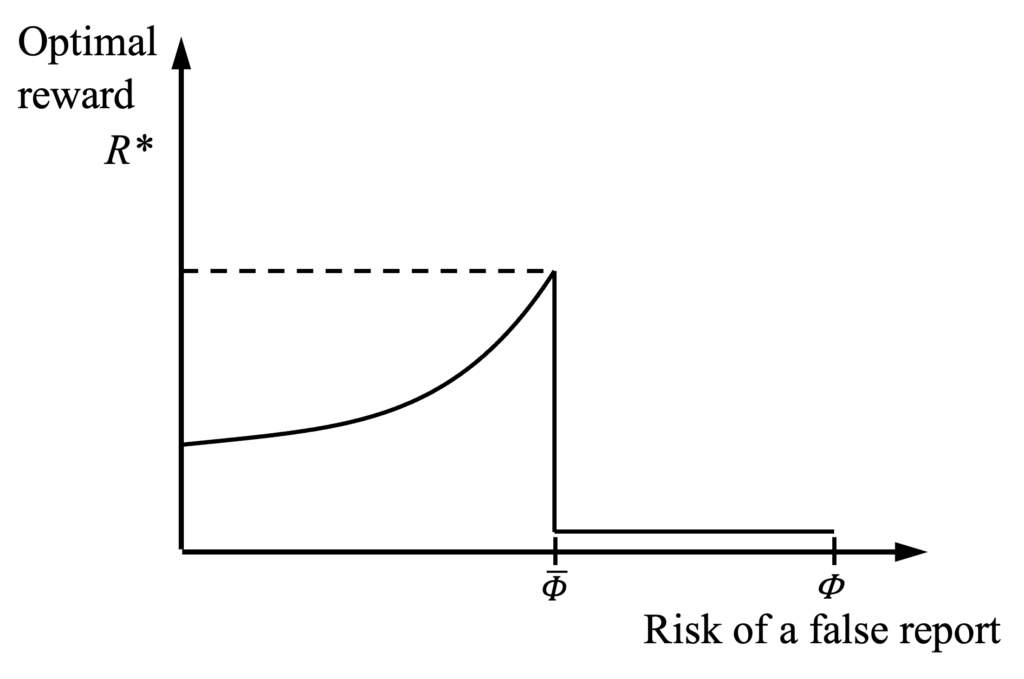

Interestingly, Givati also finds a non-monotonic association between the size of the optimal reward and the risk of a false, unsubstantiated report, as depicted by Figure 1.[115] The reasoning is as follows: With an increasing risk of a false report, it pays less for the company not to engage in misconduct. Thus, the costs of violating legal or other rules must be increased to mitigate the incentive for misconduct. This can be achieved by increasing the whistleblower’s reward, which implies a larger penalty for the company in case of misconduct. However, an excessive reward may increase the probability of false reports to a threshold level, at which whistleblowing is no longer desirable.

Figure 1: Optimal whistleblower reward depending on the probability of a false report

Givati does not consider negative reputation effects for the company in financial, consumer and labor markets after a whistle is blown and becomes public. The threat of negative reputation effects would provide stronger incentives for shareholders to install safeguards against misconduct. Thus, in the presence of negative reputation effects, the optimal reward is likely to be lower than in the Givati model.[116] Unfortunately, negative reputation effects may also occur in the case of unsubstantiated reports.[117]

There might be other negative side effects of a rewarding scheme, such as crowding out intrinsic motivation to report misconduct.[118] The prospects of earning a substantial reward paid by enforcement agencies may also undermine the insider’s incentive to report the misconduct internally, e.g. to internal control or a compliance division using a whistleblowing hotline.[119] In contrast to external whistleblowing, internal whistleblowing may reduce the probability and/or the size of reputation damages because the company may be able to correct its misconduct.

Not only Boo, Ng and Shankar but also Oelrich point out that both reward-based incentive systems and penalty-based systems, such as fines, bonus cuts or limited career prospects, may encourage whistle-blowing.[120] Oelrich argues that penalty-based systems may even provide stronger incentives based on the insights of Prospect Theory: Individuals attach a greater absolute value to a loss than to a gain of the same size, and are therefore keener to avoid losses (loss aversion). Penalty-based systems may be more suitable for internal whistle-blowing. However, enforcement agencies would find it hard to establish penalty systems for not blowing the whistle, because omission of action is hard to prove.

3. Whistleblower protection

Nonetheless, enforcement agencies can – and do – provide other means to limit potential losses of whistleblowers by different forms of protection, especially protection from job dismissal and other forms of retaliation or sanction. While limiting the personal costs of whistleblowing, mere protection does not induce the insider to expose corporate misconduct; rather it additionally requires rewards and/or sufficient intrinsic motivation. Heyes and Kapur mention three behavioral models based on insights from sociology and psychology that induce such motivation (conscious cleaning, social welfare maximizing and cost imposing).[121] Schmidt argues that a high level of loyalty to the company may trigger whistleblowing.[122]

Still, we would expect the incentives to uncover corporate misconduct to be stronger with whistleblower protection than without it. However, there may be a negative side effect: The prospects of keeping their jobs safe may induce low-quality employees to blow a non-substantiated whistle.[123] Since whistleblower protection may imply a higher risk of non-meritorious claims, it becomes rational for managers to keep a low-quality labor force, impairing the company value. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no empirical analysis to determine whether lay-off rates fall after the regulator grants whistleblower protection.

4. Unwarranted side effects of whistleblowing

Whistleblowing may lead to non-meritorious or even frivolous reporting, as Kuang et al. have shown for the U.S. [124] But there may be other side effects as well. Friebel and Guriev present a model where a division manager is able to prove earnings manipulation by an executive.[125] The poorer the division’s performance, the more likely it is that the division manager will threaten to blow the whistle. In turn, the executive is willing to bribe the division manager, e.g. by granting her a higher bonus. However, a bonus based on a bribe rather than on performance may distort the division manager’s incentives to exert effort in the first place. As a limitation, Friebel and Guriev do not allow for negative consequences for the division manager when she threatens to blow the whistle, e.g. an increased likelihood of dismissal or of limited career prospects. Negative consequences are likely to mitigate incentives for bribery and, eventually, to improve effort incentives in the first place.

IV. Empirical evidence of whistleblowing in business companies

1. Determinants of whistleblowing

a) Characteristics of the whistleblower

We mainly present empirical evidence of organizational and institutional determinants of whistleblowing. With regard to the characteristics of whistleblowers, we refer to the survey by Lee and Xiao.[126] They report that there is no or mixed evidence that whistleblowing is associated with gender, educational level, tenure or religiosity. However, older employees, employees with higher morality and employees with positive attitudes toward the company or the profession are more likely to expose misconduct.

There is robust evidence that greater perceived personal costs, e.g. from retaliation, reduce the intention to expose organizational misconduct.[127] Other studies show that the whistle is more likely to be blown in the case of more seriously perceived misconduct,[128] e.g. in the case of illegal conduct rather than unethical activities[129] or in the case of theft rather than financial statement fraud.[130] These findings may encourage the regulator to limit the costs of whistleblowing and to fine-tune whistleblower incentives with regard to the type of misconduct.

b) Company characteristics

The company’s corporate culture and corporate governance affect the incentives to report corporate misconduct. In particular, we discuss aspects of organizational retaliation and rewards.

With regard to corporate culture, there is evidence that whistleblowing intentions depend on the organization’s responsiveness towards internal whistleblowing reports, e.g. whether the recipient of the report is inquiring or not.[131] No response reduces the willingness to blow the whistle in the future or may induce employees to employ external whistleblowing channels.[132] Organizational and procedural justice,[133] perceived organizational and supervisor support,[134] and informal rather than formal policies[135] have been found to promote internal whistleblowing intentions. However, strong relational ties to team members may also discourage employees to blow the whistle when team members are involved in misconduct.[136]

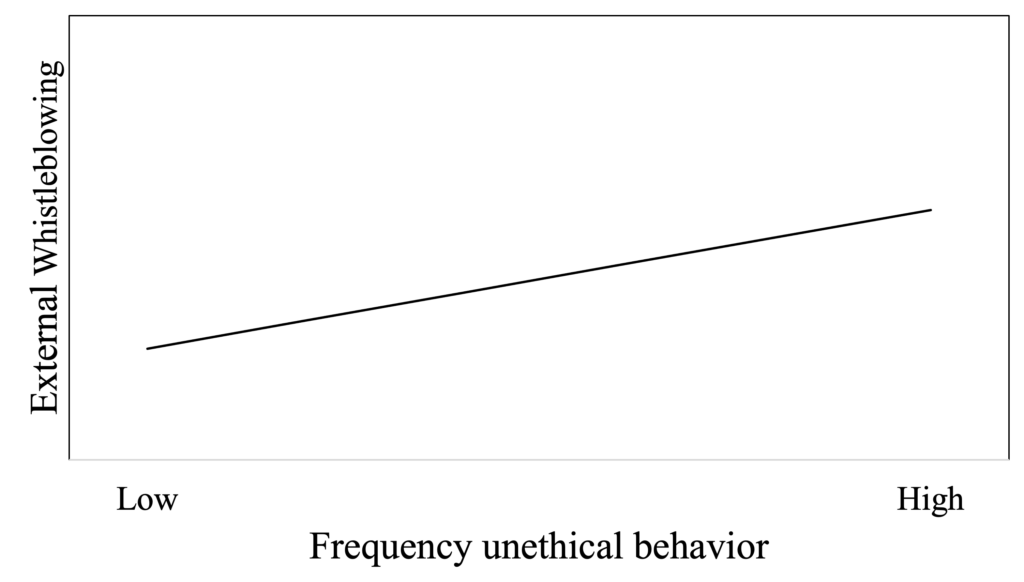

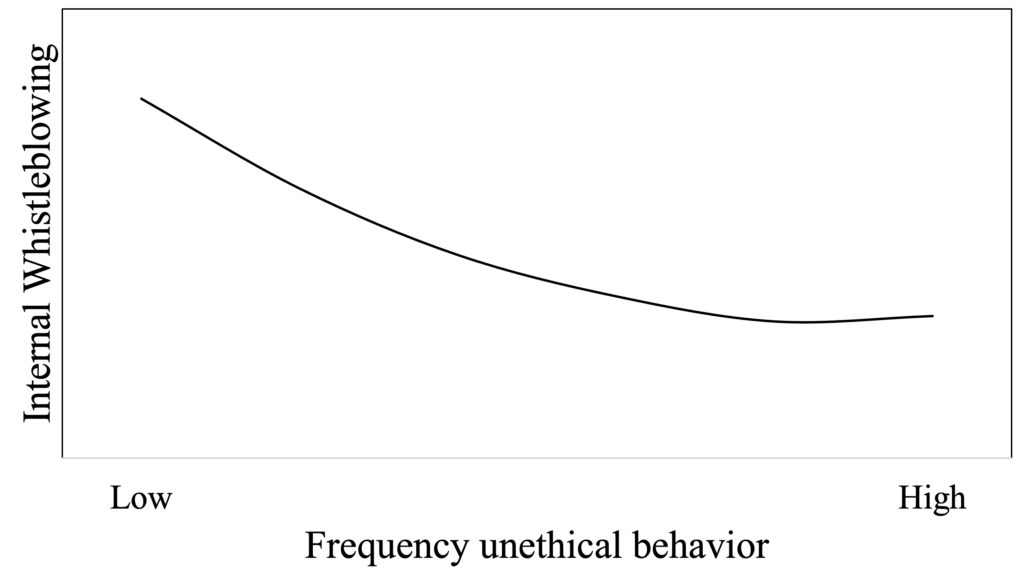

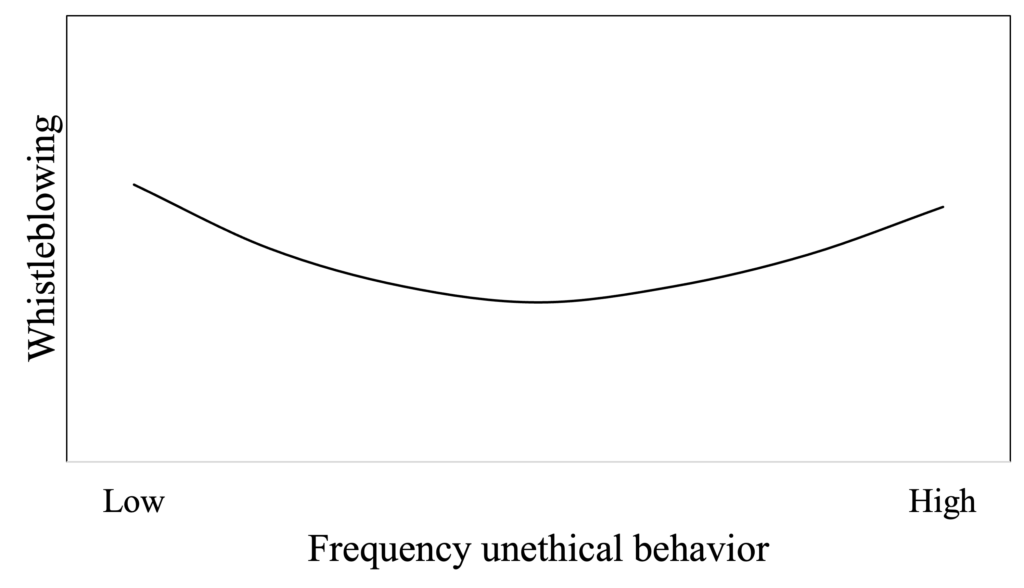

The organizational ethical culture[137] and ethical leadership[138] tend to improve whistleblowing intentions as well. However, Kaptein finds that employees are less willing to blow the whistle internally when the perceived frequency of unethical behavior in the company increases (see first graph of Figure 2).[139] Instead, they are more willing to expose misconduct via external channels (see second graph of Figure 2). The opposing effects of internal and external intentions result in a curvilinear relationship between the frequency of unethical behavior and whistleblowing intentions (see third graph of Figure 2).

Figure 2: Frequency of perceived unethical behavior in the company and internal and external whistleblowing intentions[140]

The findings of Kaptein also indicate that employees have a preference for internal rather than external whistleblowing, which is consistent with earlier findings.[141] Furthermore, Dworkin and Baucus document that employees are more likely to report misconduct externally than within the company when there is more extensive retaliation to be expected and when there is greater evidence of misconduct.[142] Consistently, there is evidence that an externally-administered reporting channel (hotline) increases employees’ whistleblowing intentions, possibly due to a higher level of anonymity and a lower likelihood of retaliation.[143]

Corporate governance characteristics also seem to affect intentions and the channel of whistleblowing. Lee and Farger provide case-based evidence that employees are more likely to expose corporate misconduct internally relative to externally when the audit committee is more independent and more skillful.[144] The reason for this difference is that companies with more qualified audit committees are more prone to install strong internal whistleblowing systems and provide better safeguards against retaliation. Wilson, McNellis and Latham find experimental evidence that an employee’s intentions to expose misconduct increase with audit firm tenure, probably because longer tenure increases trust.[145]

The corporate governance system consists not only monitoring devices, such as audits, but also incentive schemes such as performance-based executive compensation.[146] Stikeleather conducted an experiment with university students showing that more performance-based pay is associated with weaker internal reporting incentives.[147] Similarly, Call, Kedia and Rajgopal report archival evidence that external whistleblowing is less likely to occur when companies grant more (unvested) stock options to rank-and-file employees.[148] Recall that the above-mentioned model by Friebel & Guriev predicts a negative association as well, albeit in a relatively specific setting.[149] In general, the loss of performance-based compensation tends to reduce an employee’s whistleblowing intentions.[150] In a sense, the employee’s participation in the company’s success mitigates their incentives to blow the whistle, because they may otherwise lose future compensation.

Possibly more interestingly from a regulator’s perspective, financial rewards or penalty incentives at the organizational level have been found to be linked to the willingness to blow the whistle. Most of this research is experimental. Miceli and Near report early anecdotal evidence of reward schemes in U.S. companies.[151] Zhang finds that an employee is more likely to report another employee’s misconduct when the reward is sufficiently large, with a moderating effect of the principal’s perceived fairness.[152] If the principal is considered to be unfair, the whistleblower is less likely to report and more prone to collude with the wrongdoing employee. Andon et al. provide experimental evidence that financial rewards increase the propensity to blow the whistle, which is even stronger when the misconduct is perceived to be more serious.[153] With sufficiently serious misconduct, whistleblowing intentions are high regardless of whether a reward is granted or not. Butler, Serra and Spagnolo also conducted an experiment showing that financial rewards significantly increase the willingness to blow the whistle, the more so when the whistleblower is subject to social judgment than when she is not.[154]

Besides monetary rewards, reputation benefits may also encourage whistleblowing. Dyck et al. analyze 216 fraud cases of large U.S. corporations (≥ $ 750 million in total assets) from 1996 to 2004 and find strong evidence that journalists breaking a story of corporate fraud are more likely to find a better job than other comparable journalists working for the same newspaper or magazine.[155] They also find slightly improved career incentives for whistleblowing financial analysts.

Lee, Pittrott and Turner provide experimental evidence showing that monetary rewards (and anti-retaliation protection) significantly improve U.S. accountants’ internal whistleblowing intentions on financial statement fraud, but decrease internal whistleblowing intentions of German accountants.[156] They explain the results by referring to the historical distrust of whistleblowers and the strong duty of loyalty to the employer in Germany. The study by Lee et al. is important for law-making because it shows that the perception of whistleblowing differs from country to country.

Boo, Ng, and Shankar find that a reward-based career-related incentive system fails to increase an auditor’s whistleblowing incentives when the auditor is in a close working relationship with the wrongdoer; however, career-related penalties improve whistleblowing intentions.[157] Indeed, penalty schemes, e.g. dismissal or disciplinary actions, can be found with the Big 4 audit firms.[158] Consistently, Chen, Nichol and Zhou find experimental evidence that penalties increase internal whistleblowing more than rewards when individuals perceive social norms to support whistleblowing more strongly.[159]

c) Institutional drivers

Institutional determinants refer to the effects of a regulator’s whistleblowing rewards, whistleblower protection and other elements introduced by legislation.

As mentioned above, the Federal Civil False Claims Act provides high financial rewards to whistleblowers amounting to between 10 % and 30 % of the money recovered by the government when they report fraud committed against the government. The Dodd–Frank Act and the Consumer Protection Act 2010 also provide for the granting of financial rewards to whistleblowers. Pope and Lee indeed find an increasing propensity for non-anonymous reporting of corporate misconduct to an external authority after 2010[160]; Latan et al. report a growing number of whistleblowers receiving awards.[161] Nevertheless, Lee et al. point out that rewarding schemes may not have the desired effect in other countries;[162] more evidence is therefore required to determine whether rewarding schemes also work in other countries, especially in Europe.

However, not only whistleblowing laws may change incentives for reporting corporate misconduct – other changes in the institutional environment may also do so. Heese and Pérez-Cavazos find archival evidence that employees file more workplace safety complaints with the regulator when there is a significant increase in unemployment insurance.[163] Unemployment insurance reduces the cost of a job loss and thus, retaliation costs.

To the best of our knowledge, the effects of regulatory whistleblower protection on reporting propensity has only been investigated in experimental settings so far. The evidence provides mixed findings. Lee et al. document that whistleblower protection may increase the willingness of U.S. accountants to report financial statement fraud, but not the willingness of German accountants to do so.[164] Mechtenberg et al. find that introducing whistleblower protection improves whistleblower incentives, but also the incentives for non-meritorious whistleblowing because low-quality employees may be more inclined to blow a non-substantiated whistle in order to save their job.[165] Wainberg and Perreault document that graduate students with auditing experience are less willing to report violations of auditor independence and the code of professional conduct when the whistleblowing hotline policy vividly describes possible retaliations and whistleblower protection.[166] Overall, there is some evidence suggesting that whistleblower protection may not necessarily improve the detection and deterrence of misconduct.

Institutional characteristics do not only refer to legal provisions. Heese, Krishnan and Ramasubramanian highlight the importance of public enforcement by showing that whistleblowers are more likely to report corporate fraud cases to courts where the U.S. Department of Justice is more prone to intervene.[167] Antinyan, Corazzini and Pavesi conducted a survey experiment in Italy and the U.S., and additionally used household survey data from Armenia.[168] They find that higher trust in the government is associated with stronger whistleblowing intentions on tax evasion. Butler et al. find that social approval or disapproval by the public moderates the impact of financial rewards on whistleblowing intentions.[169] Bereskin, Campbell II and Kedia document that the density of social networks and the social capital in the county of the companies’ headquarters increase the propensity to blow the whistle on corporate misconduct.[170] In companies that engaged in misconduct, CEOs are more likely to be fired when employees and directors are more socially minded. Patel provides survey evidence for Australia, India and Malaysia that the country’s culture affects the willingness of accountants to accept whistleblowing as an internal control mechanism.[171] This finding is consistent with the results reported by Lee et al.[172]

2. Consequences of whistleblowing

a) Consequences for the whistleblower

Many studies investigate the consequences for whistleblowers. Dyck et al. (2010) find that journalists’ career prospects improve after they break a story on corporate misconduct.[173] However, many papers highlight the different forms of retaliation from which employees of the wrongdoing company suffer after deciding to blow the whistle. Retaliation includes co-workers’ disapproval, workplace bullying, a lack of career prospects, job loss and outright harassment.[174] Bjørkelo summarizes empirical findings showing that whistleblowers often suffer from workplace bullying, which in some cases can severely affect the whistleblower’s health, resulting in depression and symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress.[175] For a sample of Korean cases, Park, Bjørkelo and Blenkinsopp find evidence that external whistleblowers experienced bullying by superiors and colleagues more frequently than other employees, and that whistleblowers found it more distressing.[176] Support from the government or from NGOs does not reduce the frequency of bullying. Kenny, Fotaki and Scriver conducted interviews with 22 whistleblowers in the U.S. and in Europe. They document that companies often portray whistleblowers to be mentally unstable so as to create doubts about their claims.[177] Parmerlee, Near and Jensen provide early evidence of retaliation and find that organizations are more likely to retaliate against more greatly appreciated whistleblowers, e.g. due to age, experience or education, than against other whistleblowers.[178] Van der Velden, Pecoraro, Houwerzijl and van der Meulen document that mental health problems are similarly prevalent among whistleblowers and cancer patients, after controlling for demographic factors.[179] 85 % of the whistleblowers in their study suffered from (very) severe anxiety, depression, interpersonal distrust or sleeping problems, with 48 % of them reaching clinical levels of these mental health problems. Kenny & Fotaki mention that 65 % of the whistleblowers in their study reported negative changes to their mental health.[180]

More recent studies try to evaluate the retaliation costs of whistleblowers. Kenny & Fotaki interviewed whistleblowers in the United Kingdom.[181] In their cohort (N = 92), 63 % were dismissed, and another 28 % resigned, confirming the widespread fear of employees that they will be fired in case of external whistleblowing.[182] 62 % were demoted, partly before being dismissal or resigning. After having been dismissed, the average duration of unemployment was 3.5 years. Finding a new (equivalent) job was also difficult due to formal or informal blacklisting. 56 % of the cohort confirmed blacklisting activities, and 67 % experienced a salary drop after whistleblowing. Legal costs may also be significant, with respondents mentioning costs in the region of £ 1,000–100,000. Overall, after whistleblowing, the financial shortfall per annum totals an average annual amount of £ 24,817. Some respondents even report a discrepancy exceeding £ 100,000 per annum.

Dey, Heese & Pérez-Cavados investigate a much larger sample of whistleblower cases from the U.S. (N = 1,168) from the time span 1994-2012, and find that more than one-third of the whistleblowers were dismissed, 16 % experienced harassment, 10% experienced threats and 6 % were demoted. The company did not retaliate in only 21 % of cases.[183] These figures are lower than in the study by Kenny & Fotaki,[184] possibly due to U.S. rules protecting whistleblowers from retaliation. Still, the evidence supports the view that retaliation is a common response by companies to fight and prevent whistleblowing. Referring to a smaller set of whistleblowers (N = 89), Dey et al. report that they found a new job within one year.[185] 52 % found an equivalent or better job, 10 % a worse one, and 21 % became self-employed. 16 % moved to another U.S. state and 35 % changed industries. Dey et al. estimate the annual income loss to be USD 8,600, while the average reward is approximately USD 140,000.[186] Overall, they estimate the costs of whistleblowing to be lower than the figure stated by Kenny & Fotaki. Furthermore, those costs may possibly be compensated for by rewarding schemes in the U.S.

b) Consequences for the company

In the short term, companies are penalized by the capital markets. Bowen, Call and Rajgopal document an average market-adjusted stock price drop of -2.8 % in the first week after a whistleblowing announcement.[187] The price reaction is more negative (-7.3 %) following earnings management allegations. In the longer term, companies subject to whistleblowing allegations exhibited more restatements of their financial accounts, more shareholder lawsuits and relatively poor operating and stock return performance compared to companies with similar characteristics that were not the subject of whistleblowing allegations. Johannesen and Stolper report that whistleblowing on tax evasion activities at LGT Bank in Liechtenstein in early 2008 caused an average market-adjusted stock price drop of 2,2 % in the four days after the leak for 46 banks assisting foreign customers with tax evasion.[188]

Baloria, Marquardt and Weidman find that the implementation of whistleblowing programs required by the Dodd–Frank Act in 2010 had a positive effect on stock returns, especially for those companies that initially lobbied against its implementation.[189]

Call, Martin, Sharp and Wilde highlight the role of whistleblowers in improving law enforcement conducted by the SEC.[190] They find that whistleblower involvement increases the likelihood that the SEC will impose monetary sanctions on the company by 8,6 % and the likelihood that criminal sanctions will be taken against targeted employees by 6.6%. Moreover, the monetary penalties are larger and the prison sentences are longer with whistleblower involvement than without.

As a positive side effect, some companies improved their corporate governance after whistleblowing, e.g. by increasing board independence and attendance of board meetings, but only in those companies exposed by the press.[191] Wilde reports that companies targeted by whistleblowing are less likely to subsequently engage in financial misreporting or tax avoidance, at least for two years after the year of the allegation.[192] Berger and Lee estimate that the introduction of the Dodd–Frank Act reduced the probability of accounting fraud by 12-22 %.[193] Nonetheless, audit fees have not significantly changed, even though audit risk should be lower after passage of the Dodd–Frank Act. In contrast, Kuang, Lee and Qin document that audit firms charge higher audit fees to clients that are subject to external whistleblowing allegations regardless of whether these allegations are substantiated or not.[194] In fact, this is another cost of non-meritorious reports.

Bowen et al. and Wilde used whistleblowing cases from 1989-2004 and 2003-2010, respectively, i.e. before the Dodd–Frank Act came into force. It would be interesting to study whether the market sanctions and/or the companies’ responses to whistleblowing are more pronounced after the Dodd–Frank Act was introduced. In addition, there is lack of similar studies on European whistleblowing cases and on cases related to non-financial misconduct, e.g. with regard to environmental misconduct or violations of worker safety.

c) Consequences for the economy

To date, there is little empirical evidence on the costs and benefits of the existence and type of whistleblowing regulation from a society’s perspective. Admittedly, this is a challenging task. A handful of papers address specific, yet important, aspects. Johannesenand Stolper find that whistleblowing on tax evasion at LGT Bank in Liechtenstein in 2008 caused a sudden flight of deposits from tax havens, possibly mitigating future tax evasion incentives.[195] Lower tax evasion would enable governments to reduce tax rates and to stimulate economic activity. In fact, many countries have established tax-related whistleblowing programs, but they generally yield only modest tax collections.[196] Nevertheless, a tax-related whistleblowing program established in Israel in 2013 deterred companies from tax evasion, at least as long as the program was effective.[197]

Du and Heo highlight the effect of corruption on companies’ willingness to invest.[198] They find that investment levels are lower in U.S. states that are more prone to political corruption. However, after the Dodd–Frank Act was enacted, investment levels increased, especially in states with more corruption.

V. Conclusion